author: Emily Jacobi

date: 2019-08-28

slug:

title: The Amazon is Burning — How, Why & What Can We Do?

wordpress_id:

categories: – blog

image: https://miro.medium.com/max/2400/1*_9jUH9IR20jZFQogd2H0jA.jpeg?q=20

–

In the past week, news of fires in the Amazon Basin spread through social media threads & news sites, sparking outrage, debate, resignation, denials and more. Maps and satellite images have been shared, but the take-aways haven’t been universal. Is fire a normal occurrence in the Amazon, this year’s blaze overhyped by the media? Are the fires, like melting Arctic Sea Ice, a tragic result of climate change? What are the socio-political factors at play? What’s really happening, what’s at stake, and what is there to be done about it?

As an organization that partners directly with Amazonian indigenous groups using maps, ground data & satellite images to protect their ancestral forests, these questions hit close to home for the Digital Democracy team & our partners. In this post, we seek to shed light on what’s really happening in the Amazon — both the fires and the political situation that (quite literally) ignited them. Where are the maps and data sources that can help us make sense of the news? What are the actionable steps we can take to be allies to Amazonian Indigenous Peoples who are on the frontlines of protecting the world’s largest rainforest? Why should we pay attention?

First, who are we, and why are we writing this?

Digital Democracy is a technology NGO, focused on supporting grassroots groups to leverage technology to defend their rights. We work at the intersection of human rights & environmental justice. For the past 6 years we’ve primarily worked in the Amazon, with frontline indigenous groups who have invited us to work with them. With partners in Brazil, Columbia, Ecuador, Guyana & Peru, we provide trainings & ongoing support to local groups, and co-create technology to meet their needs. Most of our programs focus on mapping & environmental monitoring, using technology that is accessible (ie cheap & easy to use) & works offline.

Every day, our local partners are putting their bodies on the line to document threats to the Amazon, and our international partners are amplifying these messages with campaigns, maps & satellite imagery. We are heartened by the outpouring of interest in the Amazon at this moment, and seek to illuminate not just the current reality of the fires, but the broader context that makes them so dangerous. The unfolding crisis in the Amazon is about much more than fire, and the planet’s future depends on us understanding what is happening in order to collectively advocate for change.

A Closer Look at the Fires & the Burning Season

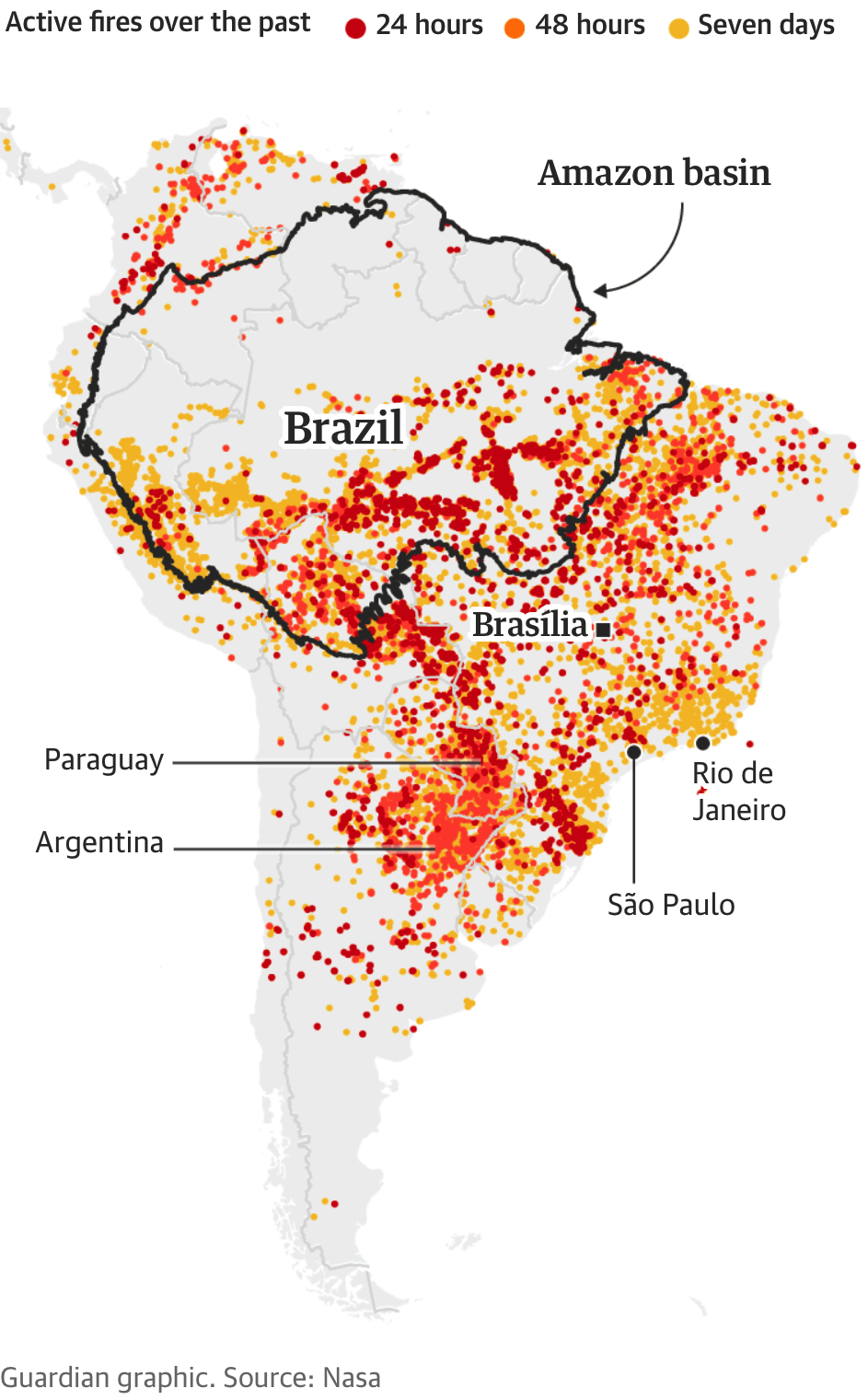

Tens of thousands of fires are raging across the Amazon basin, primarily in Brazil & Bolivia. The New York Times estimates the fires in Brazil to represent a 77% increase from the same period in 2018. Many of these fires are happening in areas that are already being used for agriculture, but what is particularly concerning is the high concentration of fires showing up newly clearcut areas, and where they are spreading into existing, or intact, forests.

From a thorough Guardian Q&A published on August 23:

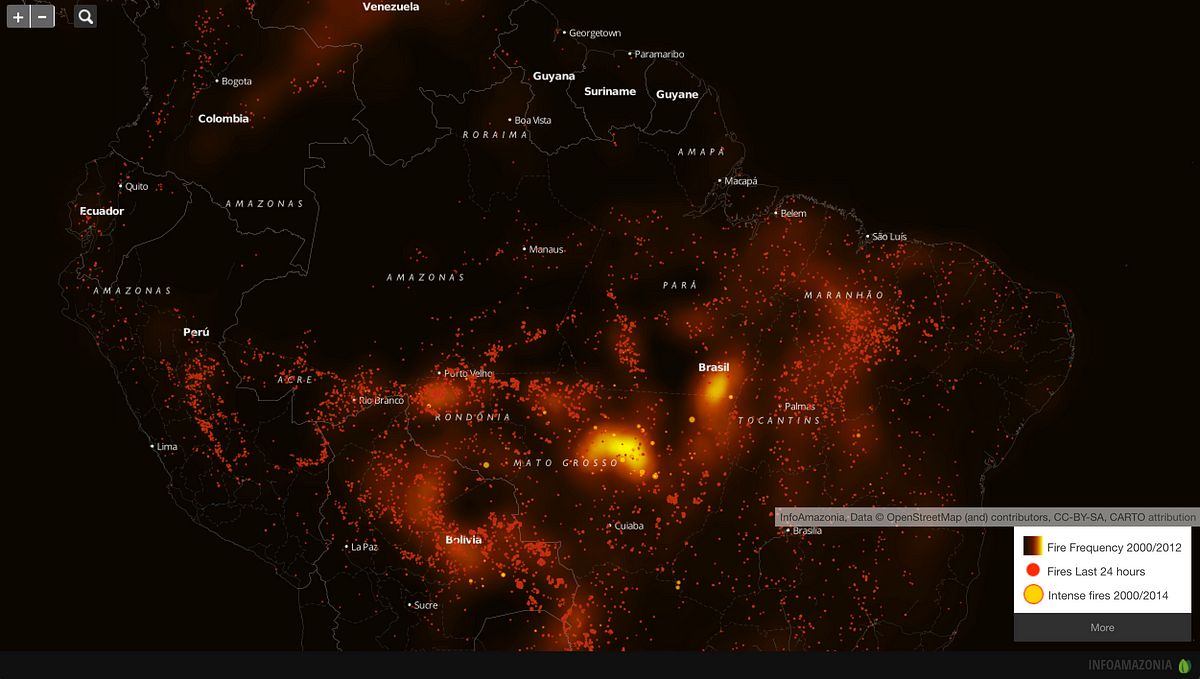

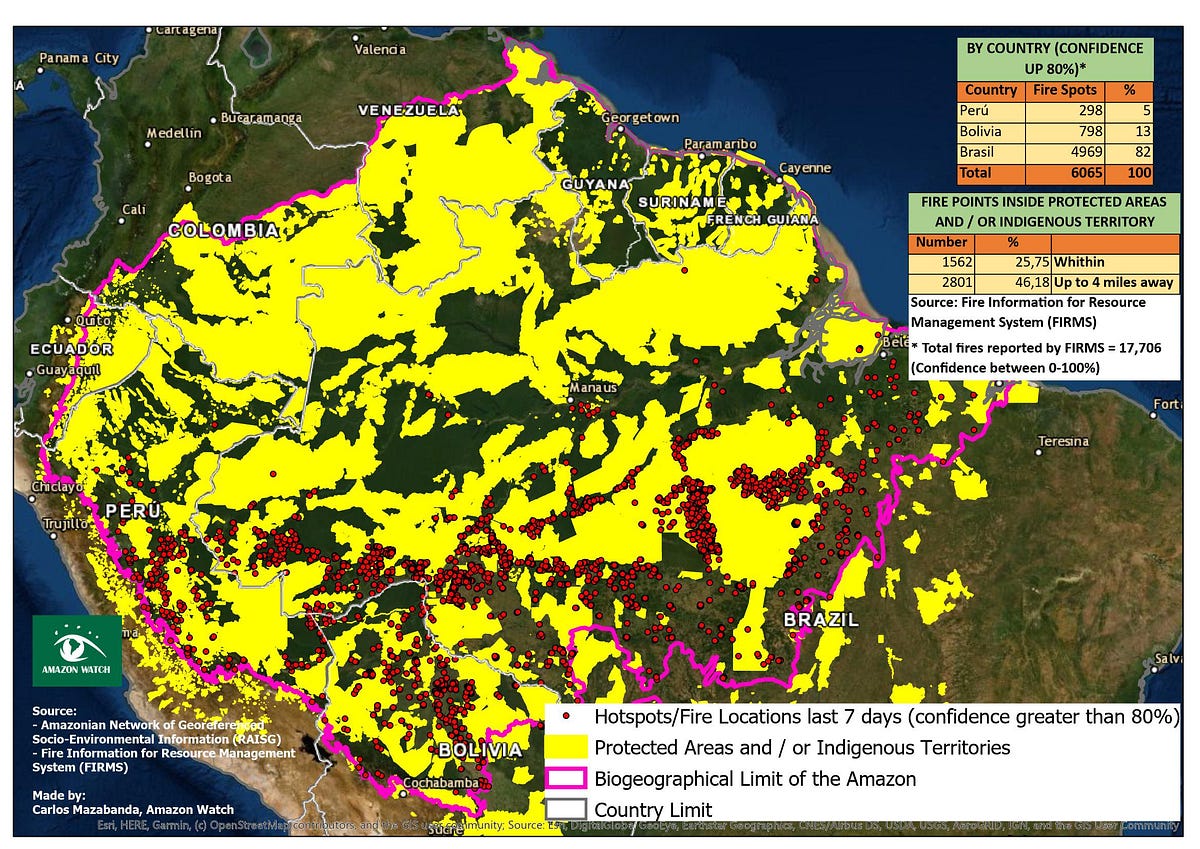

As the map shows, fires are not only happening in the Amazon basin — as dry season begins in southern South America, fires are happening across the region. There is reason for concern beyond the rainforest — up to 800,000 hectares of Bolivia’s “dry” Chiquitano forest have been devastated by blazes, and Chile is facing its worst drought in six decades.

The focus of this post is on the fires currently happening in the Amazon basin. What do the fires mean for the human cultures & ecological life sustained by the rainforest? What impact might they have on the critical role that the Amazon plays in filtering oxygen & supporting the planet’s weather systems?

To see fire map data yourself, you can explore the interactive map & fire data on the Global Forest Watch platform, and read their informative blog post on the current fires. The InfoAmazonia portal is also an important aggregator & resource for Amazon-focused maps.

How does a rainforest burn, and what can be done about it? What’s really happening?

As a resident of California, I’ve seen and studied the role of fire as a management tool, and critical part of the ecosystem of the North American West. Trees in savannah areas & northern forests have adapted to fire being a normal part of their cycle.

But not so in the rainforest. The lush, wet conditions inherently prevent against fires, so wildfires are not a natural occurrence in tropical forests. Fires start in areas that have already been deforested, and even then are usually set by humans, not sparked by accident. However, fire itself is not inherently bad — in the Amazon it is a traditional farming tool to release nutrients into the soil. But as farming has gone from small scale to covering huge swaths of former forest, the phenomenon of fires during dry season has rapidly increased. It’s important to note that one of the factors right now is that August is the beginning of fire season — fires will most certainly increase over the next few months, both as areas that have been clearcut are set on fire to burn the undergrowth, and as farmers and ranchers ignite previously cleared areas to renew soy fields & grazing areas. As fires feed on recently clearcut areas, they can grow large enough to burn into intact forests, a cycle that then makes clearcutting easier next year.

What makes this moment particularly concerning is not that fires are happening, but where they are happening, how many are happening, and the political context that explains why the rate has increased so early this dry season, compared to recent years.

Read more about the science behind fires & how they impact the rainforest in this in-depth piece from The Conversation.

What’s up with Deforestation?

Deforestation across the Amazon takes many forms. For example, some of the partners we work with are challenging illegal logging in Peru, illegal mining in Guyana, oil drilling and gold mining in Ecuador. Across the region causes of deforestation include roads, agriculture, palm oil, and land grabbing. The many threats to the forest are rooted in the same thing: Colonization, theft of indigenous territories & resource extraction.

In other words, deforestation is not something that “happens” in the Amazon— it is something that is done, willfully, by humans.

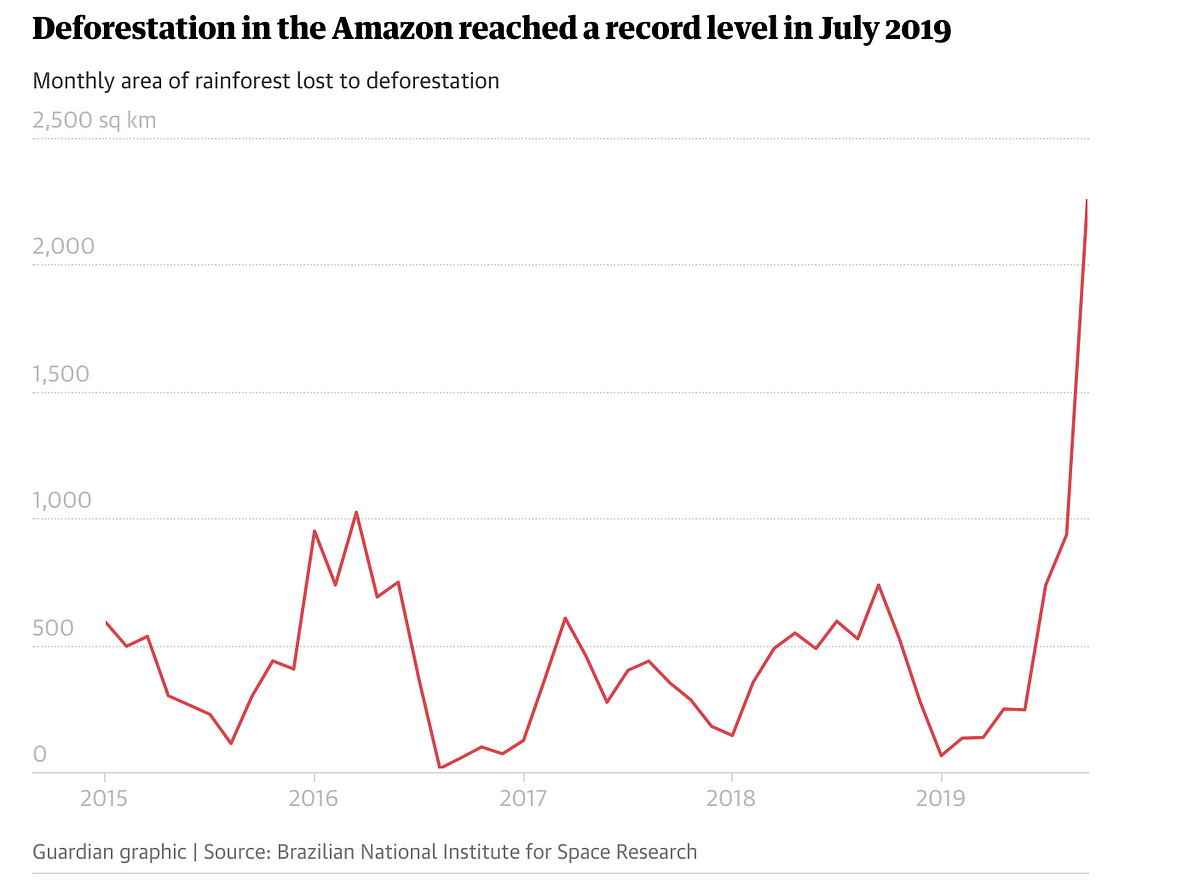

The 1970s saw the first deforestation on an industrial scale in the Amazon, and for the following three decades forest loss rose dramatically. After hitting a high point in 2004, concerted efforts — both within Brazil & internationally — began to decrease the rates of deforestation — to be clear, the forest was still reducing in size, just at a slower rate. However, those numbers began to rise again over the past five years, as politicians in Brazil reduced political protections, and the demand for economic growth pushed for roads to be built in new territories. This is not simply a Brazil problem — global demands for cheap soy & beef encourage ranchers and farmers to claim more and more rainforest for grasslands and fields. This year, that trend towards higher rates of forest loss has spiked dramatically. In July, an area the size of Manhattan was cut down every day.

For more on historic deforestation trends across the Amazon, see this article on Mongabay. For more on the current increase in deforestation, read this Guardian Q&A published on August 23. Graph from the Guardian:

Why the sharp increase in deforestation this year?

This dramatic attack on the world’s largest rainforest is no accident. It is an attack not only on the forest but specifically on the indigenous people who depend on it.

Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, who took office January 1, is a climate change denier who openly advocates for seizing indigenous held territory for private business. In 2017, while campaigning for president, Bolsonaro vowed:

“If I become President there will not be a centimeter more of indigenous land.” — Jair Bolsonaro

In 2016, speaking to Congress about Raposa Serra do Sol, Indigenous Territory in Roraima, northern Brazil, Bolsonaro declared:

“In 2019 we’re going to rip (it) up. We’re going to give all the ranchers guns”

Not dissimilar to US President Trump, Bolsonaro has staffed his cabinet with agri-business leaders, gutted environmental protections and stopped enforcing protections on indigenous & ecological reserves. These actions have led to predictable — and disastrous — consequences. The Bolsonaro government, hostile to NGOs, has severely undermined indigenous rights and is opening up the Amazon to more deforestation and land grabs than ever before. As Christian Poirier, Program Director of Amazon Watch stated on August 21:

“The unprecedented fires … (are) directly related to President Bolsonaro’s anti-environmental rhetoric, which erroneously frames forest protections and human rights as impediments to Brazil’s economic growth. Farmers and ranchers understand the president’s message as a license to commit arson with wanton impunity, in order to aggressively expand their operations into the rainforest.”

This is not just speculation. Brazilian newspaper Brasil de Fato reported on August 21 that ranchers were deliberately setting fire to forested/protected areas, emboldened by the Bolsonaro administration:

“Cattle ranchers and soy farmers are deliberately setting trees ablaze to cut down forests and create pasture. In Pará state, farmers and ranchers declared a “fire day” (August 10), coordinating a massive burnoff of trees to draw the government’s attention, claiming that “the only way to work is by cutting down trees.”

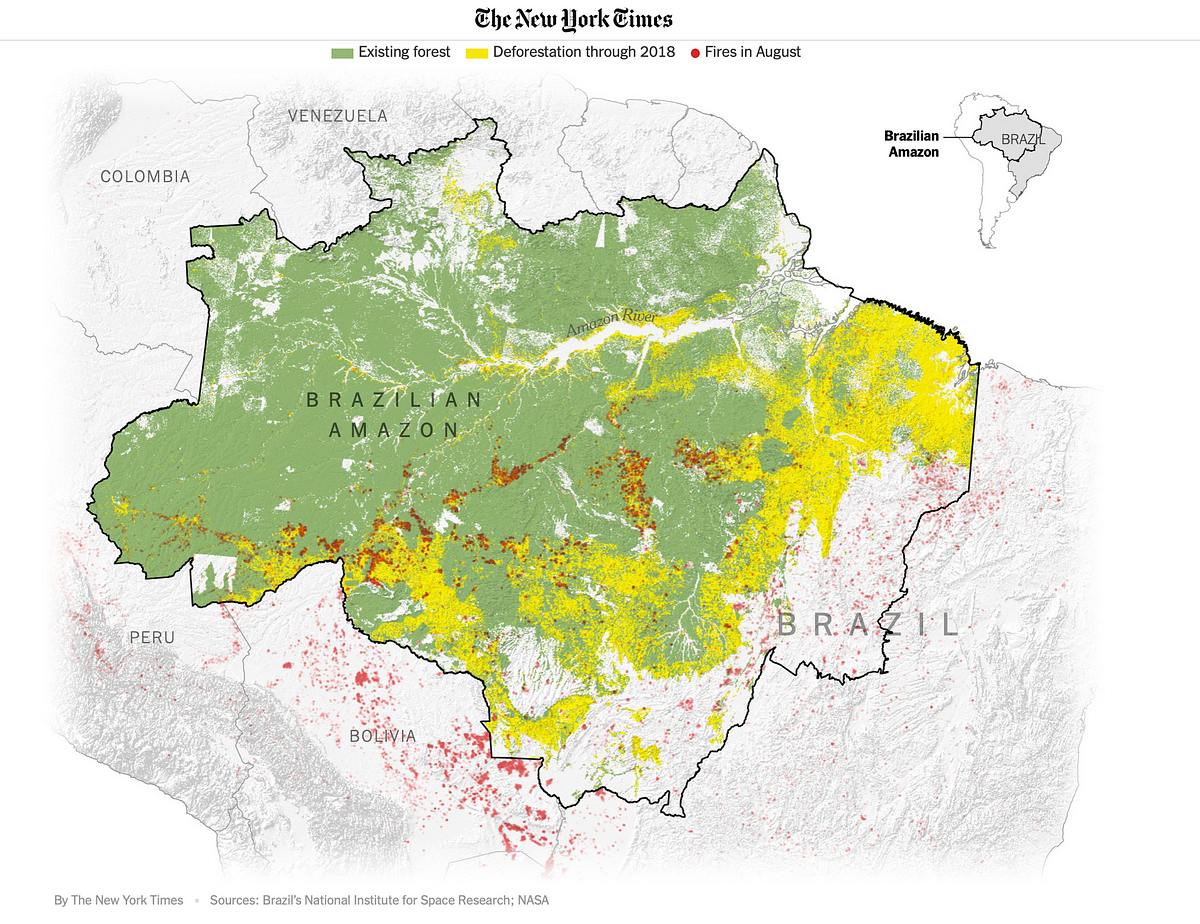

This context is what makes the next map particularly concerning. Given that some 20% of the Brazilian Amazon is already deforested, it is not surprising to see fires in widely deforested areas, for agricultural purposes. But for so many of our indigenous partners, the edges between forest & so-called “developed” areas are the most dangerous, because this is where they are defending their lands against the dramatic efforts to colonize and clearcut the land.

As the following map from The New York Times demonstrates, many of this month’s fires in Brazil are happening precisely on these edges — in the map, red fire dots show up along the sides of green (existing forest) areas, not so much in the center of yellow, previously deforested areas. This map clearly tells the story of how fire is being used to expand the agricultural frontier, into primary rainforest:

The following map from Amazon Watch has even greater detail, overlaying recent fire data with protected & indigenous territories. A close look at the map shows just how many of the fires abut protected and indigenous areas (yellow). This map also highlights the many fires in the Amazon region happening in Peru & Bolivia:

Where is the evidence from the ground?

While the various maps & data visualizations help to show one piece of what’s happening, maps & satellite imagery alone can’t tell the full story. In this moment, we believe it is critical to center & amplify the voices of local people. Our partners Amazon Frontlines are working to get financial support to communities in the direct path of the fires. Here, an indigenous brigade of Xerente peoples in the Brazilian state of Tocantins are cutting firebreaks to control a burn in their ancestral territory:

With deforestation enabled & emboldened by the Bolsonaro administration, Amazonian indigenous peoples are mobilizing. Earlier this month, indigenous women from across Brazil (plus allies from other Amazonian countries) marched in Brasilia:

What’s at stake is nothing less than their survival. As Rayanne Cristine Máximo França, an indigenous Baré woman from northeastern Brazil told the CBC:

“We are facing a process of genocide with this government, also a process of ecocide. They are killing us every day; they are killing us with the fire that is happening, they are killing us when they displace us from our territories, when they invade our territories.”

On August 23, our partners Greenpeace Brasil conducted a flyover of the heavily impacted states of Pará & Rondonia, where indigenous people like the Karipuna have been hard hit by the attacks. Danicley Aguiar, Amazon Campaigner at Greenpeace Brazil said:

“It’s urgent and necessary to put an end to this vicious cycle while we still have time. During a flyover last Friday (23 August) we could see the consequences of Bolsonaro’s government anti-environmental agenda: extensive deforested areas, surrounded by smoke, showing the advance of industrial agriculture into the forest. Unlike what the Bolsonaro’s government claims, the wave of fire sweeping the Amazon is linked to an increase in deforestation in the region.”

Meanwhile, COAIB (Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon), has expressed extreme concern about the situation:

“The record rates of deforestation and outbreaks of fire are a consequence of the anti-indigenous and anti-environmental genocidal speeches of this government. Loggers are taking our land and irresponsible landlords are taking advantage of the weakening of environmental surveillance to advance into our homes.”

The full COAIB statement is viewable here, in Portuguese, Spanish, English & French.

Who’s at fault, and what really is at stake?

As terrible as Bolsonaro’s statements, actions and impact may be, he didn’t emerge from a vacuum. His administration simply represents some of the worst aspects of a global economic system dependent on exploitation and extraction. It is this system which must be changed in order to halt deforestation in the Amazon. And anyone reading these words on a telephone, tablet or computer is in some way connected to this global system. There is work for all of us to do in educating ourselves on what’s really happening, and yes, changing some of our individual practices. But most of all we need to apply collective pressure to change laws and policies in order to halt the drivers of deforestation and change the flows of capital that encourage it.

In this sense, the cause — and the effect — of the Brazilian fires is both local and global. The Amazon is called the “lungs of the earth” for its role in carbon storage and oxygen production. It also plays a critical role in global climate and weather regulation, sending rain as far as California and the midwestern United States.

Alarmingly, the Amazon is nearing a deadly tipping point. Currently, at least 17% of the Amazon has been deforested. Scientific estimates vary, but many models demonstrate that somewhere between 20–40% deforestation will trigger a feedback loop called “dieback,” whereby the rain cycles disappear, turning jungle to degraded savannah.

So what really is at stake? Nothing less than the cultures, traditions and worldviews of the millions of Indigenous people of the Amazon, the wildlife & ecosystems of some of the most biodiverse areas of the planet, and the critical role of the rainforest in regulating the global climate, and mitigating the worst effects of climate chaos.

What then, can we do?

There are immediate steps to take, and there is the longer term, movement-building work to support indigenous sovereignty and address climate chaos.

1. Follow the leadership of Indigenous Peoples

It’s no accident that places where biodiversity is highest are also the places with the greatest diversity of human languages and cultures. Indigenous rights are the cornerstone to protecting nature, and are the best antidotes to the 500 plus years of industrialization and colonization that have led our species to the brink of planetary disaster.

Effectively addressing fires and deforestation in the Amazon means centering the leadership of the Indigenous people who live there, defending their right to sovereignty over their ancestral homelands, and uplifting their voices and efforts. Indigenous people have defended the Amazon against colonization and exploitation. In the context of Brazilian President Bolsonaro rejecting aid foreign aid, recognizing and defending indigenous sovereignty is both the most moral & effective approach. It is true that the fate of the Amazon shouldn’t be decided by outsiders — it should be decided by the people who have co-evolved with it for thousands of years, who protect the forest because they recognize that it is their grocery, their library, their cathedral, the source of life.

Take for example this powerful video from Menkragnoti Indigenous territory in Para, Brazil:

Video via Xingu +, shot by Kamikia Kisedje

While the world prays for the Amazon … we’ve gathered all Xingu’s indigenous and riverine peoples, and we want to say that we will resist for the forest. For our way of living. For the future of our children and grandchildren. For the health of the planet.

For this we say no to mining on our lands. No to deforestation. No more invasions and disrespect. No more pesticides in our rivers and food. No more criminal fires in the forest. We from Xingu are connected with you. We are on the frontline. And we need your support. Join us in this fight.

2. Give money directly to frontline indigenous groups

Our close partner Amazon Frontlines, along with Land is Life, are raising money to support the indigenous coordinating body of the Brazilian Amazon, COAIB, to get resources directly to frontline groups. In the past few days they have shared stories of how these funds are being used to support local patrols and fire brigades, where indigenous people are working to prevent fires from spreading into their territories. Donate to their Brazil fund, 100% of which will go directly to COAIB.

This weekend, the Earth Alliance announced the Amazon Forest Fund, a commitment to give away at least $5 million to directly affected organizations. Earth Alliance is co-chaired by Leonardo DiCaprio, Laurene Powell Jobs & Brian Sheth. (Note — Digital Democracy is a prior grant recipient from the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation, which is now part of Earth Alliance.) Earth Alliance is calling on others to donate to the fund, which goes directly to support protecting the Amazon. Initial recipients of support include:

- Instituto Associação Floresta Protegida (Kayapo)

- Coordination of the Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB)

- Instituto Kabu (Kayapo)

- Instituto Raoni (Kayapo)

- Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)

3. Support the work of indigenous led patrols, mapping & monitoring programs

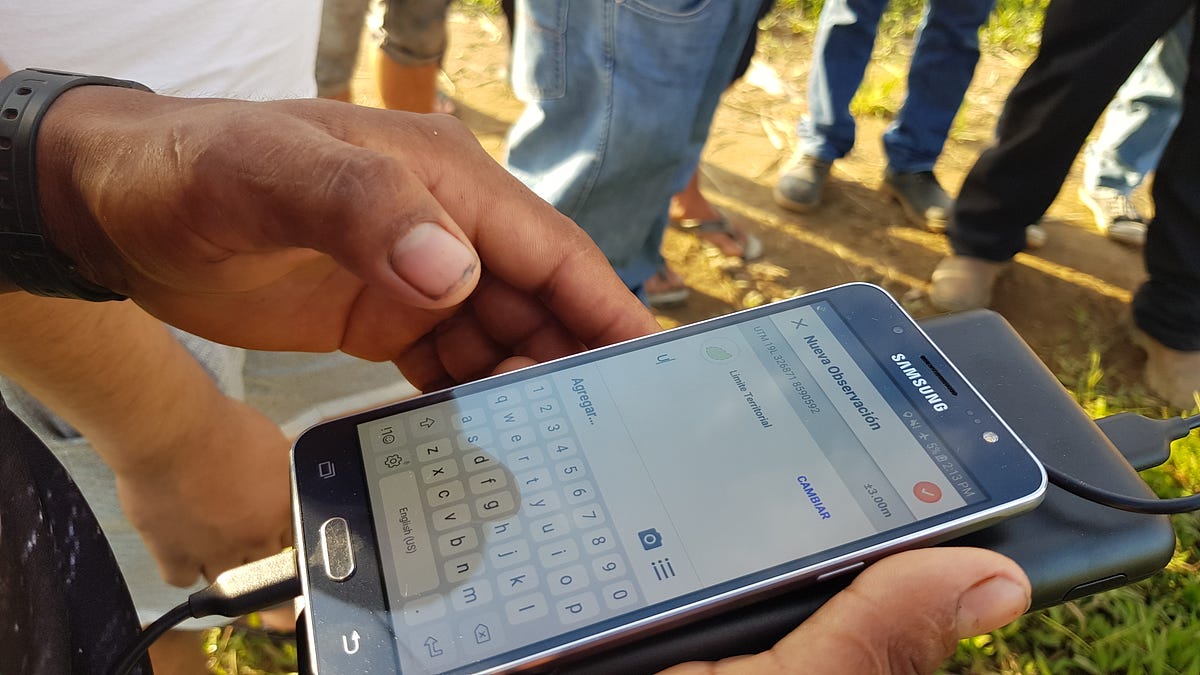

Across the Amazon, some of the most effective actions of frontline defenders include mapping efforts to gain legal title over their land, local patrols or “guardias” where indigenous people are defending their territories from exploitation and illegal activity, and ongoing environmental monitoring programs to document when crimes are committed against the forest, as well as the rich biodiversity of local areas. These programs are critical to local communities, and it’s why our partners ask us to support them with the tools and training they need to run these programs effectively.

Indigenous-led mapping & monitoring programs work, and we’ve seen it firsthand with our partners. In Ecuador, the Waorani people won a major victory in court this year, leveraging maps as part of a broader legal strategy to protect 500,000 acres of their territory against oil concessions. In Peru, we’re working with the Ejecutor de Contrato de Administración de la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri (ECA-RCA), who are the guardians of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, the largest reserve of its kind in Peru, which demonstrates the power of indigenous co-management of territory. Organizing village-to-village and using smartphones, drones and satellites, ECA are protecting more than 400,000 hectares of forest while providing alternative livelihoods to their local communities.

Our team has devoted ourselves to co-building tools with our partners like the Waorani & ECA, because we’ve seen firsthand the victories our partners achieve when they are able to manage information on what’s happening in their territories themselves. But for indigenous groups like these to be successful, they need initial investment — money going directly to indigenous-led organizations to support mapping & monitoring initiatives, as well as for gear to go on patrols and document what’s happening. On the tech side, we at Digital Democracy welcome supporters & collaborators to help us further build out our tools so they can fully function for local users without outside support. Investing in infrastructure like Mapeo, our offline mapping & monitoring tool, is a way to ensure that indigenous communities in the Amazon & elsewhere have the tools they need to meet the ongoing challenges they face.

Notably, the work of land patrols & participatory mapping can yield big victories, but it is also extremely dangerous. As Global Witness reports, it is dangerous work to be an environmental defender. Last year an average of 3 per week were killed across the globe for their brave efforts to protect their homes and halt extractive projects. And yet, across the Amazon and indeed the globe, brave individuals and communities are working to protect their lands despite the risks.

Read more on the Amazon Frontlines blog about the land patrols of one of our Ecuador partners, the Kofan people of Sinangoe. Land patrols were key to their recent legal victory to halt mining in their territory, and they are currently focused on making their own map of their territory.

4. Recognize original peoples & honor their land rights

At the end of the day, land patrols, mapping & environmental monitoring are all in service of one thing — the land rights that ensure that indigenous people can maintain their way of life and the ecosystems they depend on in their ancestral homelands. If we believe that indigenous people are the key to protecting the biodiversity of the Amazon — and they are — then we must also stand up for indigenous land rights around the globe.

Why should Brazil respect indigenous rights if Europe, the United States and Canada do not? The work of acknowledging whose land we are on, supporting efforts to return land to indigenous peoples, and recognizing indigenous rights to determine what happens on their territory is work that every one of us can do, every single day. And, we can advocate for the legal changes that will better ensure indigenous land rights in the future. Wherever we live, we must support local, native-led efforts to protect sacred ecosystems.

Visit Native-land.Ca to learn whose land you are on. Check out Resource Generation’s toolkit for Land Reparations. Support groups like the Sogorea Te Land Trust in Chochenyo Ohlone territory (now called Oakland, California) where I contribute an annual “voluntary” land tax as an Oakland resident.

5. Keep your eyes on the Amazon & connect the dots

What’s happening is complex, and deserves our attention. I’ve linked to many organizations and indigenous communities in this piece — all of these are worth following. For maps and data, we specifically want to call attention to the Brazil-based InfoAmazonia, as well as Global Forest Watch and Amazon Conservation’s Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP). For advocacy & news from local partners, Amazon Frontlines, Amazon Watch & Greenpeace Brasil are three of many groups sharing critical information.

Connect the dots — how do our consumption patterns contribute to Amazon deforestation? Join movements like Rainforest Action Network and call upon our governments to hold businesses accountable for where they source materials, whether wood or agricultural commodities. We can ask where the ingredients in our food come from, especially palm oil, soy (used for both humans and livestock) and beef. We can also support more sustainable development initiatives, especially those that provide right livelihood for native communities using their lands in traditional ways. Whether we have been aware of it our not, our lives are interconnected with the guardians of the forest.

We can also pressure our governments to take immediate & critical steps towards addressing climate change and the broader system that enables it, the same system which is fueling resource extraction in the Amazon.

September is going to be a crucial time, as world leaders gather in New York for UN Climate Week, with youth, indigenous and other civil society leaders joining to pressure governments to take decisive action. I’m particularly excited for the first-of-its-kind Peoples’ Summit on Climate, Rights and Human Survival, organized by Greenpeace & Amnesty International, because the time is overdue for the human rights & climate movements to recognize that environmental justice & human rights are intrinsically interlinked.

But you don’t have to travel to New York to advocate for change. The National Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) has called for international supporters of the Amazon to organize a global day of action. Wherever you are, you can join the day of action for the Amazon on September 5, and the global climate strike on September 20th.

Whatever happens with the current fires in the Amazon, it is clear that the deeper emergency is deforestation and theft of indigenous land. May the fires be a light that shines our collective attention on this ongoing crisis, and may the heat of their flames spur us all to the move our feet out of the fire, and into a more just future.

As the Brazilian journalist Eliane Brum wrote for The Guardian on Friday,

“The Amazon is the centre of the world. Right now, as our planet experiences climate collapse, there is nowhere more important. If we don’t grasp this, there is no way to meet that challenge.”

Let’s work together to meet that challenge.

About this post: Emily Jacobi is the Executive Director of Digital Democracy, a US-based NGO that supports marginalized communities to use technology to defend their rights. This blog post was inspired by talks within Digital Democracy and with our partners, including research and analysis by Dd’s Technology Director Gregor MacLennan. All of the images, maps, and graphs in this piece are linked to their original source. This post was deeply informed by our partners and colleagues including COAIB (Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon), Greenpeace Brasil, Global Forest Watch, the All Eyes on the Amazon coalition, Amazon Watch, Alianza Ceibo and Amazon Frontlines.