author: Mark Belinsky

date: 2010-10-07 18:32:18+00:00

slug: googles-internet-at-liberty-conference

title: Google’s Internet at Liberty Conference

wordpress_id: 2248

categories:

If you were to Google "Internet", "freedom", "security", "privacy","blog" and pull together the people and organizations that make up the top hits of the search, you would have the Internet at Liberty Conference, hosted by Google on September 20-22 in Budapest. A venerablewho’s whoof people involved in the worldwide discussion surrounding Internet freedom, this conference was an amazing opportunity to catch up with some of my favorite people who are fighting for the rights of humanity online, to hear updates from the internet governance forum that occurred the week before, and for strategizing new and innovative projects.

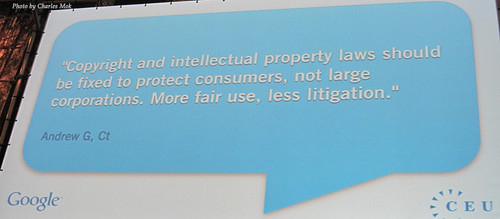

The themes of the conference centered around how the internet can be used to advance human freedom at a time of great uncertainty about the future. After Secretary Clinton’s Internet freedom speech last January, this has become a more participatory conversation, used to hammer out solutions with government actors, people who are interested in upholding human rights, those putting out the examples of their actions, and additional companies that have remained silent on the issues regarding the rights of their users.

The Chatham House Rule was enacted at the Conference, meaning that no one could be photographed or quoted without permission. I appreciate that Google made this simple but important gesture, given that many people were endangering their own lives to attend this conference and to be a part of these conversations. I’m often upset with the lack of caution taken when people take photos of friends who are dissidents in foreign countries. It’s frightening what a little social network analysis can reveal for interested authorities. And it’s a tool that is becoming less and less complicated and out of reach for some of the World’s most repressive regimes.

Google vs Facebook was a sight to be seen. Google has planted it’s feet firmly in the ground that information is a human right and they appear to be doing everything possible to lead by positive example. Facebook on the other is frequently beaten up by bloggers offended by their policies and more recently by mothers upset by their censorship.

Google’s approach to dealing with governments has been to respect the privacy and security of its users without offending the governments with which they operate. Tangibly, this has meant censoring locally where "necessary" without giving up the identity of it’s users, unlike groups like Yahoo! that have given information to Chinese authorities, which has led to subsequent arrests. Their goal is to refuse removing any information from the Internet but rather making it a 2-step process to get to when deemed inappropriate by a government. They might remove content from the local domain, say Google.th in Thailand, but users can still get to google.com in just 2 clicks, to get the content they desire. They’re decentralized in that way, and it’s working for them.

Facebook cannot employ this same "top level domain filter". Facebook users don’t have the ability see a different version of my profile, depending on what country from where they are viewing it. Instead, Facebook makes a "value judgment." Having been to their offices, I believe that this means that a space of 500 million people is ruled by the values of sandal-wearing twenty-somethings in California. People with no accountability. The greatest audience outrage I’ve seen recently is the breast-feeding mothers campaign that launched in response to censorship caused by violating these "values". Ironically, Sunil Abraham tweeted an outlandishly false statistic that in the USA 12,000 women are actually arrested for breast-feeding per year. This falsity became the most popular message to surround the ial2010 hashtag on Twitter. But the real issue is that Facebook hasn’t provided due process. Like when malls became places for free speech and arbiters of that speech, now Facebook is the intermediary. There is a need for procedure enabling people to appeal. One idea suggested was a community of governance for the site, where users can decide upon the values therein. A shocking proposal to make the site democratic, rather than the benevolent dictatorship it currently resembles.

It’ll be interesting to see how other sites deal with this issue, particularly ones with geopolitical implications like OpenStreetMap. Already there have been arguments over the the names of geographical locations, such as the area in Southwest Asia known most commonly as the "Persian Gulf", which Iraqis refuse to call it, and over military areas in Russia. Will the site be blocked in certain countries and will they choose to alter content in order to ensure that the service is available to all users around the world, even of slightly modified?

Sami Ben Gharbia of Global Voices framed a lot of the discussion at the conference with his article "The Internet Freedom Fallacy and the Arab Digital Activism". According to him, the US should never have gotten into the conversation about the Internet in the first place, because now it is a more dangerous place for the Arab bloggers that used to experience it as a free space devoid of political meaning. I take a firm stance that someone needs to defend those freedoms, and the more countries that stand to defend article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights stipulating information as a human right, the better.

The themes and fears spoken about during the conference played out directly afterward. When I arrived to NYC, I got word that my friend and conference-mate Jiew was arrested upon her re-entry to Thailand. While Sami theorized that it was her attendance at the conference that led to the arrest, it was actually due to a two-year old charge under Les Majeste, for comments posted on the independent news website Prachatai, which she manages. Our team quickly launched a campaign to set her free by raising the money for her bail, and through outreach online, pressuring authorities to change their policy. The State Department stood back, Google offered help if necessary and her network of friends and colleagues were able to bail her out of jail within 24 hours of the arrest. Had it escalated further, and it will soon, as she’s scheduled to go to court in February, it’ll be curious to see how the different actors from the conference will help her cause. Already, EFF has issued a statement.

In the wake of the Haystack debacle (again, open source FTW) and the Wikileaks Afghan maps controversy, it’s important to be mindful of the fact that governments are starting to increasingly clamp down on the crucial tools that protect and preserve individual freedoms because they don’t have examples to the contrary to work with. I’m still hoping that Handheld Human Rights can serve as this tool, showing that circumvention and security tools are helping people and governments based on the UDHR alike. The national security conversation at the conference framed where these future discussions are going to go.

A technologist helping to bring wikileaks legal protections in Iceland explained that "Iceland has no national security laws because it has no army." It was broken down further, described as a "A cayman island for data centers" an analogy to the financial industry. "Like libel tourism in UK" noted one of the Conference’s panel hosts. A concern was raised that similar to tax-havens, there will still be international pressure on small countries by bigger ones to give up the protections they claim to uphold. Governments are certainly gong to be looking to that kind of "front door" method, while also exploring back-door techniques, getting companies like RIM to give law enforcement a special key to data.

Another attendee related these theories to the realities of his own work. He explained that there are not only ethical considerations, but also technical ones. Sharing information opens ones ability to get hacked. "Once a week I call a company and ask if they want their secret stuff back" on the internet, it’s not only opening data to those one thinks they are.

An outspoken citizen rights activist from Vietnam brought it down to the ground, arguing that national security used to silence people in countries like hers. However, this is not usually done within an international legal framework of "security" as outlined in the Johannesburg Principle. Countries can’t invoke national security without specifics that are enforced through UN mechanisms. A problem is that violations of these standards are addressed "eventually." The panel host shot back, asking whether that is "good enough for the people of Afghanistan."

Tor, no stranger to this conversation, especially as one of it’s employees can’t currently travel, complained that there isn’t yet a digital due process that is noticeable to citizens. Can they "knock on the door before entering"? Because currently we don’t do that with data. But at the same time, we currently rent, and give the landlord the ability to open the door.

The architecture and control of the Internet is still far away from most citizens and governments alike. In the corporate infrastructure of wires and bytes its obvious that we all have to play nice, but the solutions are still a long way off. Perhaps we need to look to the past and look into the development of deeds. In addition, right now, there is an exciting development, those looking at the governance of international waterways and other shared bodies to learn lessons for the shared network of the net. Or maybe netizens will rise and plant the flag of the Internet firmly at United Nations Plaza. First, the world will have to agree on the design.