author: Karissa McKelvey

date: 2020-06-22

slug:

title: Renarration and Accessiblity: T B Dinesh on Localized Knowledge in Rural

India

wordpress_id:

categories: – blog

image: https://images.digital-democracy.org/assets/dinesh3-1600@2x.png

–

T B Dinesh is a community media activist with a background in Computer Science. The recent focus of his work is on storytelling methods and encouraging people from marginalised communities to tell their own stories and document their ways of life. T B Dinesh is a founder of Janastu in Bangalore, India. Janastu is a non-profit that has been providing free and open-source software solutions and support to small not-for-profit and non-governmental organizations (NPOs/NGOs) since 2002.

The following is a shortened transcript of a conversation we had in the spring.

Karissa: What are you working on these days?

Dinesh: Our big slow-moving project is focused on local knowledge and local Wi-Fi mesh networks in rural and remote areas in India. 60-70% of India is illiterate — for all practical purposes, they cannot read or write — which describes most of the population.

We’re focused on how to make local knowledge tools that do not expect any kind of literacy. We are building an audio internet where most of the publications are audio/video, stories and visuals. The term ‘hypermedia’ means linking one piece of knowledge to another, like HTML does. We are taking this concept and doing it with audio/visual.

For example, we give village girls a community radio device. If she has a geometry equipment box, we put a Raspberry Pi inside and do group recordings.. If she has a phone she can use it to transmit, but the system doesn’t require a phone. The radios encourage group activity and collaboration while phones are personal.

She just hits a button and starts talking, she doesn’t need to print, put it on a palm leaf or paper or inscribe it on a rock. Two generations later someone can listen to it. It does not ask who you are — if you are a rural person or tribal or educated. It’s an amazing new equality.

Listen to stories from Namma School Radio.

A media making kiosk-studio, including a microphone and monitor.

The caste system is based on enslaving a large number of people as sacred knowledge propagators. These propagators were forced to memorize the “Word of God”, and regurgitate it in another space and time. The Brahmins came up with many creative systems to preserve knowledge that relies upon millions of people, generations upon generations, just so something could be orally replicated with precision.

When you look at the axis at any rural school, of 100 children studying, only 5-10 will be able to read and write, go to town, and get a basic job as an errand boy or cleaner. Most others will experience an invalidation of the self, as a typical school curriculum can only validate one who is comfortably literate.

They want a way to validate themselves by just talking rather than feeling like they are lesser beings by not knowing how to read and write. I’m not saying they shouldn’t be taught, but to require it invalidates a person, and it’s time to change that.

Karissa: In typical software development practice based in Europe/US, literacy isn’t really thought of as a key component of accessibility. Cell phones are designed for people who are literate.

Dinesh: We looked at the web accessibility guidelines, and all of them expect you to be similarly educated–even if you are blind. If you have eyes but cannot read, there is no web accessibility standard that can be used as a guide. Now if 70-80% of your country is illiterate, this is a problem. Most of these guidelines are made by Western people. Most of the research is coming from the west. They focus on localization (translation), but accessibility needs to go beyond that.

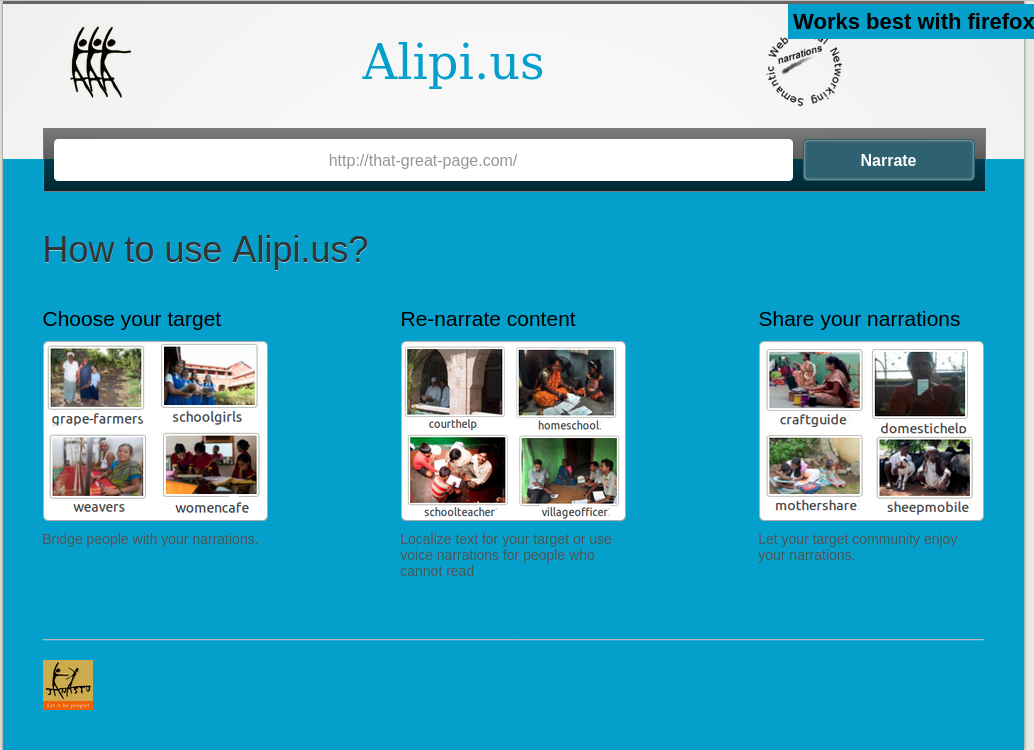

For us, accessibility means something different. It means a social semantic web. By social we mean that people contribute towards accessibility needs. By semantic I mean the first paragraph can be retold by someone else–while keeping the abstract intent of the content–for another audience. The second can be retold to another’s needs, and so on, establishing relations between the original and the retold parts using attributes such as the target language, identifier tags or a target community context. This network can go as big as you want, every document can be elaborated and connected.

So if it’s a text-heavy document, how do you make it accessible to people who can’t read? We call this _Renarration (Sweet Web). _The web documents should have the kind of structural framework that facilitates alternate narrations. That’s how we started this work — can I take a text document from your blog, take it to my village and make it a visual story for them? What are the actions that I need to take? What do I highlight?

So we work with a web annotation framework. Annotations are another layer over the web. We don’t assume anything is automatic in this process. But this doesn’t take a lot of time. it doesn’t need to be an all or nothing task – typically, it’s more likely that someone provides an alternative narrative that is suitable for the person they want to share the document with.

For example, the minimum wage act that we’ve worked on — many people who need it probably can’t read it. A simplified English version of the act was published 30 years later, but otherwise, it’s in legal language. The easy to read version helps the local Indian NGOs understand it. They need a simplified version in order to explain it to their stakeholders – ie., what the act is about, and to provide a general understanding of what minimum wages mean.

Karissa: What led you to start working on local knowledge?

Dinesh: We started trying to make it easy for NGOs to manage the community knowledge they assimilate when we worked on a platform called Pantoto – communities managing community knowledge. Most of the NGOs we were working with were afraid that their work would get stolen. We tried to explain that if they put their work out on the Web, a reader would be able to look it up and know that it was originally published by them and thus realise if someone was misappropriating their content. For original content, it matters that you put it out there, publish it.

As we were working with smaller groups in different villages, we started to focus on content accessibility issues for their specific needs.

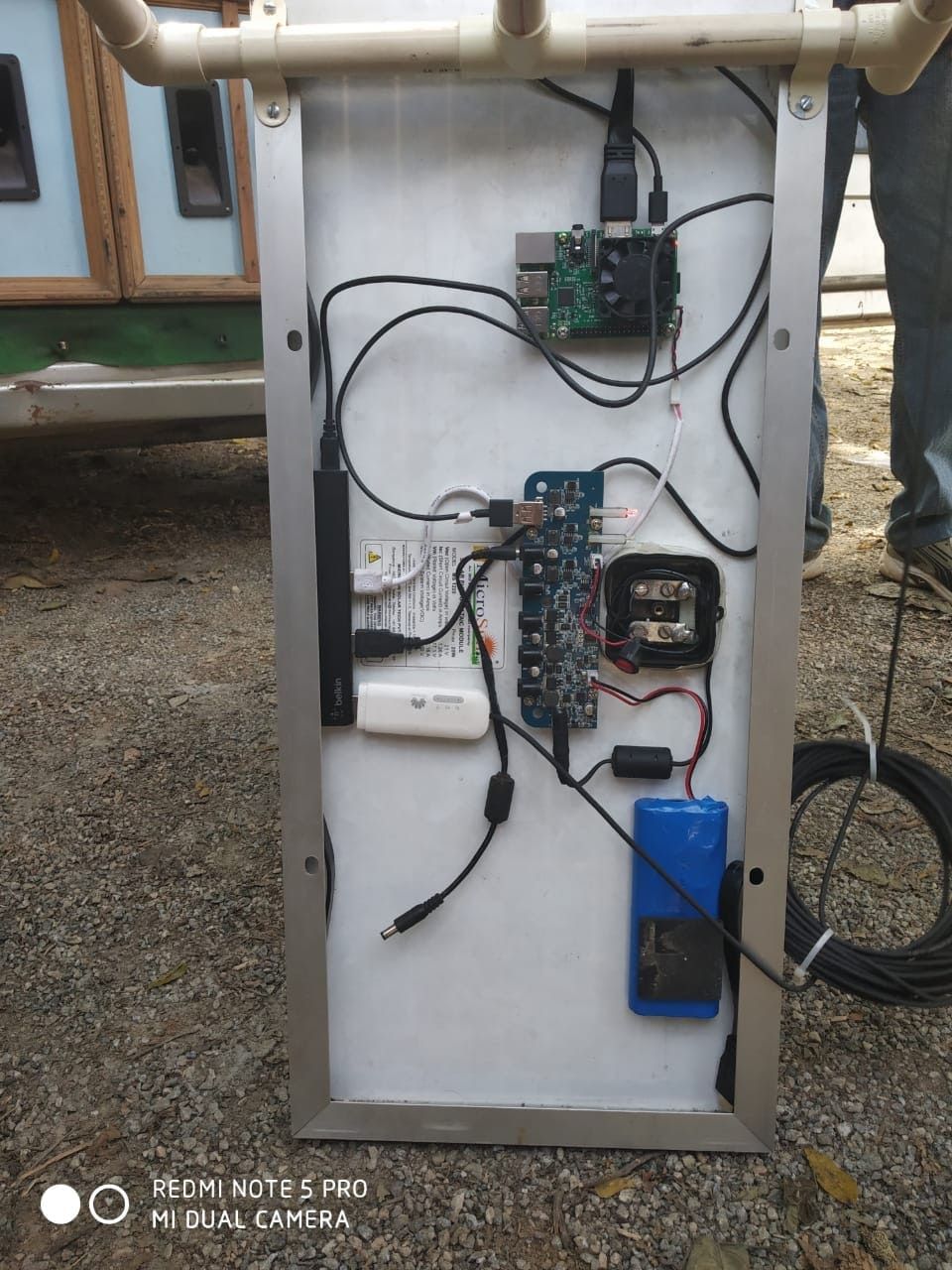

Now, after almost a decade, our work is an attempt to address aspects of accessibility completely from the ground-up, starting with low-literate communities who find it impossible to publish on the Web. We build these Raspberry Pi based audio recorders and leave them in a village craft center. They can record messages to the community, and to the other groups that have access to the Pis. It’s a community mesh-radio. It’s important that no one needs to be a coder or even literate to publish or manage their data.

, Durgadahalli, Tumkur Dist. 2018*](https://images.digital-democracy.org/assets/dinesh3-1600@2x.png)

Craft Cluster, Durgadahalli, Tumkur Dist. 2018

Karissa: What are some key challenges that you’ve had to overcome while building out this project?

Dinesh: One challenge we have is how to store all of the information. Everyone has something to say, sing, recipes, stories, lessons … the many ways we learn. But how do we store it? We have created a Wi-Fi mesh network of archives that are locally available on the mesh. Then, all of our tools help people annotate their content so that it’s discoverable and navigable.

All of their data will stay on their own Raspberry Pi – they don’t need to push anything out to anywhere else. We are cheating a bit, by syncing in the background that’s encrypted, just in case they were to lose everything. Once it’s out on the mesh archive, it’s sharable on WhatsApp, or can be synced with another Pi in a different village.

Another big question we have grappled with is when the Internet is available, what should be exposed to the community outside of the local mesh network? First, you have a community device, it’s basically reflecting what happens in the real world. Even if it’s hosted in their office, sometimes people aren’t convinced it isn’t hosted outside. For example, if you’re opening in a browser, then it must be on the internet and accessible outside!

In the radio studios under lock and key, we don’t depend on the internet. We aren’t really using an internet cloud to synchronize everything, but we try our best to have multiple backups. It’s encrypted but based on the source node, you can get all your data.

An old telephone booth device that has been converted to either record audio or listen to community radio recordings over the wifi-mesh

A solar panel with an omni antenna serves as a 24/7 online media server for the WiFi-mesh based community radio activity in a rural and remote context.

Karissa: What is a concrete example of local knowledge gathering and its impact?

Dinesh: We helped create a document about the Raika bio-cultural protocol (BCP). This village is tending to their camels with an 1000-year-old protocol for living with animals and taking care of them. When there is a top-down law, someone will say, “they don’t know what they’re doing.. we need to tell them.” To those at the top, if it’s not written down, it doesn’t exist. They think that the local community is destroying the environment.

This “BCP” work focuses on making written legal documents with the community so that the people at the top, like policymakers, can read about their protocol. Because the document we create is for those at the top, it is written in English. So the document also needs to be profusely re-narrated in different ways so the community can understand them.

Different people contribute to the whole document. You can also add audio per paragraph, and see the translation. The software keeps a connection to the original so that you can have that authenticity, even if it’s different and not about translation, about re-narration, it has a backlink to the original. This is one way to address the huge question of how to tell a new story from an existing one.

We are trying to use it as the new standard to do all the annotations. Every edit and re-narration is authored and attributed to the people who contributed.

Karissa: What is the tension between the global Internet and what’s accessible locally?

Dinesh: People want to use WhatsApp, it’s a natural ambient technology. We are not competing with WhatsApp. What we are doing is likely not going to be taken over by any of these big companies. Publishing locally, to the people next to you, is not what these companies are interested in doing. If you talk to a neighbor, the whole narrative is so different.

For example, if you make a computer game with your village, you’re not going to get a gun and shoot all your neighbors. You see this everywhere — as soon as I am anonymous, I can use bad words to harm someone I don’t know, loud and clear. This relates to everything on the Internet, even the online harassment of women. Where does it come from? Disconnection? The thrill?

This is why logging in and authentication becomes so important for these larger internet companies. When you go to the village, it’s the last thing you need, or rather, you can’t even do it. Logging in without internet connectivity just to authenticate somebody, but why?

Students at rural public school working together and listening to a podcast on the mesh.

Karissa: Yes, the concept of ‘authentication’ and ‘anonymity’ does change so drastically when you’re from a small community where everyone knows everyone else. It also seems like you’re engaging in educational practice, teaching journalism and technology.

Dinesh: To be honest, it’s more educational than their experience at school and very validating. The syllabi for their typical education is set in the capital of the state and pushed down to every village without any contextual knowledge, so that the state has a common metric for who knows addition, multiplication, etc.

They want to know that people have actually learned this. If the schools teach a more flexible, contextual syllabus, they can’t test them. It’s all very puzzling.

What we’re doing is not about limiting them to a set standard, it’s about giving them access and opening them up.

Karissa: Do they share their stories between communities?

Dinesh: Our collective has a community radio van, with a solar roof and WiFi, it can go everywhere. This van has a studio in it where people can cut, edit, and publish the stories. When the van comes back to the community, it synchronizes. These are initially in a “raw” bucket and then moved to curated buckets to be picked up by anyone. If you record something in your Pi, it syncs whenever it connects to the network.

, Bengaluru)*](https://images.digital-democracy.org/assets/dinesh8-1600@2x.jpeg)

Community Radio activity center and camp setup (Source: jaaga.in, Bengaluru)

We do automatic sync so people realize they are not alone in this. They realize there are other people that will help with the re-annotations. In the radio editing studio, it’s a more powerful Pi, some box that is a little more powerful. Whatever comes out of this box is published and shareable. Otherwise, it’s private. We don’t share names other than what’s coming out of the audio.

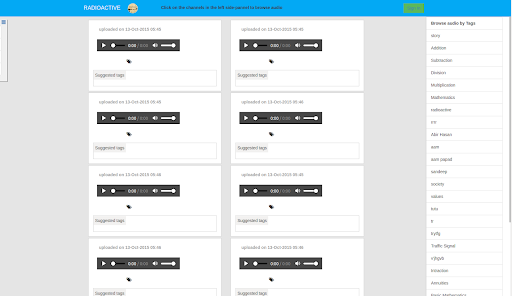

Papad — http://papad.pantoto.org/

We ask the community to contribute and suggest tags for the audio files. There are lots of pieces like this, just scratching the surface of what we are doing. Most of all, it’s about using the non-typical approach. We don’t insist on web forms, for example. It’s contributed metadata, it’s not self-proclaimed metadata, added after the fact by many people.

If they do that, they become something and get an understanding of how the world works. If nothing is handed down, they can’t change the world.

Learn more: