author: Jen Castro

date: 2020-02-24

slug:

title: Reflecting on Bringing MAPEO to Northern Peru

wordpress_id:

categories: – blog

image: https://images.digital-democracy.org/assets/andoas-group-shot-fun-1600@2x.jpg

–

Three perspectives on our work in the field…

In November 2019, three members of the Digital Democracy team travelled high up the Pastaza River in the Peruvian Amazon to the small oil town of Andoas, near the border with Ecuador. The purpose of the trip was to train Indigenous land defenders to use MAPEO for collecting and sharing evidence of oil spills on their territory.

The community federations in the Pastaza, Tigre and Corrientes river basins had long been anticipating this training. They have been documenting oil contamination and reporting it to their local advisors and Peruvian authorities since 2006. Over the years, they’ve used various technologies to gather better and more precise information to try and improve company and government responses to their environmental monitoring efforts. The local teams have learned to use GPS, camera traps, drones and smartphones. However there were still gaps between community needs and the available technological solutions, for example there was no way for those collecting information to share data between themselves, without needing the internet. These locally identified needs were some of the original inspirations behind the creation of MAPEO Mobile.

After two years development time and more than a year of field testing in the Amazon by the community park guards of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve in Southern Peru and the Kofan community guards in Sinangoe, Ecuador, MAPEO was ready to bring to the teams in Northern Peru, as a integrated environmental monitoring system for smartphones and computers.

This is how it went:

Jen Castro

We have been planning this training for over a year in collaboration with advisors from PUINAMUDT and researchers from the ISS (International Institute of Social Studies at Erasmus University) who have been supporting the federations with political organizing, strategizing and environmental monitor training. One of our key goals for the trip was to bring new equipment and tools to help the monitors collect data more easily, view it locally, and share it in situations where there is little to no internet connectivity. Another goal was to provide practical training to the monitors, building their confidence in using the technology, and most importantly training them to train others how to use MAPEO. One of the best ways we as an organization can offer long term support is to help build capacity for local partners to continue their work and skill development autonomously.

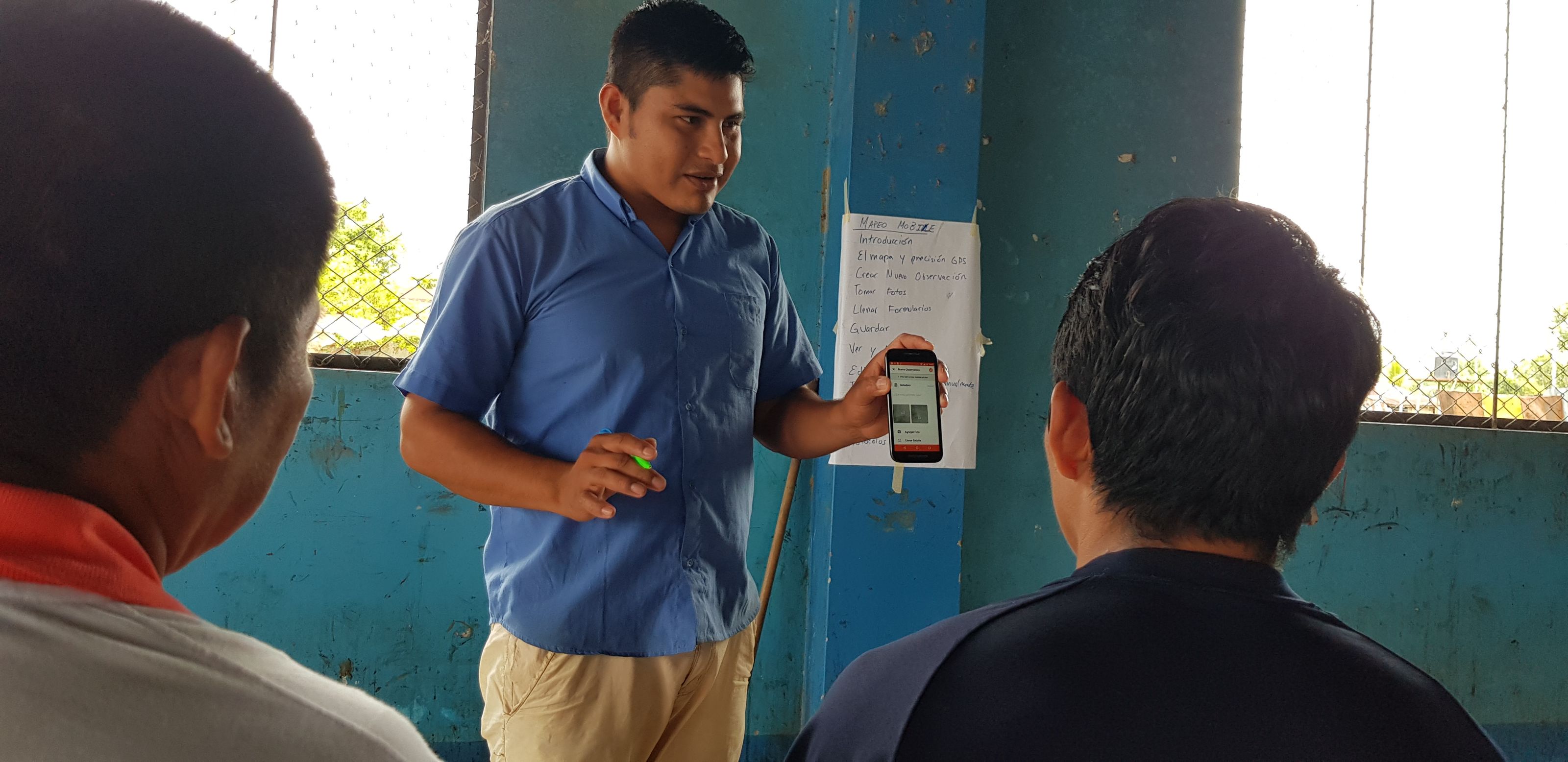

My role as program coordinator included designing and organizing the training program and materials, and facilitating the workshop so to make the most out of our 6 days together. We worked in breakout groups to build skills in various technologies, my focus being to train more experienced community monitors to use MAPEO Desktop to synchronize data with MAPEO Mobile. I knew from experience that learning this workflow gives users a good foundation for doing mobile to mobile sync with ease. After the monitors saw how quickly they could get the evidence they collected with MAPEO Mobile onto their laptops and also look at the data from their peers on a detailed map of their territory, they were even more motivated to be trainers of MAPEO Mobile. I helped them create a training agenda and they practiced training each other and then supported each other to co-facilitate, through a “teaching is learning” methodology.

Building lasting confidence with new technology is one of the most important things we can do as a technology organization. I was in absolute awe seeing freshly trained monitors training their peers with such enthusiasm and I was so inspired to see one group of monitors being trained in Quechua!! I also learned that deeply listening and stepping back in these gatherings is critical to keeping the power where it needs to be, with the local communities. I am only a visitor after all, offering what I can and then returning home. Our partners are land defenders in Northern Peru, protecting their ecosystems, living on the frontlines of a decades-long battle with numerous oil companies and they know more about what they need than I ever will. If I travel all that way, what I offer needs to be what they are asking for and it better be good.

Karissa McKelvey

This was my first active full-length training in a remote area in the Amazon. I was very excited to learn about the work that community monitors are doing to protect their ancestral territories. Their commitment to justice and care-taking of their land is spectacular and inspiring. My role as a technologist was to lend a helping hand and provide everyone with technical assistance and support. My main responsibility was to ensure that MAPEO was functioning as intended, which included listening in Spanish to monitors speak about technical issues and ask questions about the technology, then working out details about what happened, and helping them succeed in their task. I’ve been learning Spanish since I was young, and have done many short and longer immersion trips, but this was only my second trip to the field where knowing the language was a necessity to get the work done. Being able to unlock this ability over the past few years allowed me to connect more with the monitors, hear their stories of struggle and resistance, and better serve them in accomplishing their goals with the technology.

Gregor and I troubleshooted many personal phones and computers, as well as improved the application. As monitors reported unexpected behaviors in MAPEO, we were able to fix these problems and return to the training the next day with a new version of the application. I then created special configuration files for each federation, which was a tedious but rewarding process. This allowed all of their sensitive data to be encrypted with other land defenders collaborating with PUINAMUDT, ensuring that someone outside of the community monitoring project cannot access the data unless they have the special configuration files and keys we generated during the training.

I also helped with the “train the trainers” portion of the event, where I walked around to different monitor pairs and groups to help answer any questions about how the technology works. It was inspiring to see monitors training and helping each other after only a couple days of training. This extra time we spent working with them in a collaborative and supportive fashion really seemed to be an important part of this particular training. This peer-to-peer learning was immensely effective and allowed them to grow their capacity to be more self-sufficient with the technology. It proved to be a successful model for the development of trainers.

Gregor MacLennan

I first travelled to this region of Northern Peru in 2006, at the request of the indigenous communities who were frustrated by the continual denial by the Peruvian state and the oil company — PlusPetrol — about the ongoing impacts of contamination in the region. Argentinian Pluspetrol, and before them, Occidental Petroleum from California, USA, had been pumping oil from this remote region since the 1970s. Their operations left a trail of environmental devastation in its wake, including leaking pipelines and waste water deliberately dumped in the rivers that local communities depended upon for fishing and drinking water. On that first trip the communities requested training to use cameras to document the ongoing oil spills, as the government consistently denied there was any contamination, despite the hundreds of gallons of crude which were being spilt each year.

Over the years the communities developed a network of skilled local environmental monitors who documented new spills as they happened, uncovered hidden pits of crude deep in the forest, and successfully brought pressure on the government and the oil company to clean up the mess. The community monitoring teams have shown amazing dedication, often working without funding and with minimal, aging equipment. On the November trip alongside many new, enthusiastic faces were experienced monitors who had participated in trainings over 10 years ago.

A major challenge for the monitors has always been organizing gathered evidence in ways that they can present to the government. They have deep local knowledge, and notebooks filled with valuable information, but it has been hard for this information to reach the cities and government meetings where it is most needed. It was amazing to return on this trip and offer some real solutions to the challenges they have been facing: new equipment, including smartphones that work simultaneously as a GPS, camera, mapping tool and powerful data collection device; and the MAPEO toolkit, which allows them to collect and share data offline.

It was also very powerful to observe the training method developed by my colleague, Jen, to train-the-trainers. The more experienced monitors quickly picked up the new tools thanks to the investments we’ve made in design and usability, and it was incredible to then watch them teach others, in their own native language Quechua, how to use the tools and collect the evidence needed about new oil spills.

The trip was also a learning experience for me, as Technical Director of Digital Democracy, to think through how we need to improve the MAPEO toolkit. Ultimately we want to reduce dependency on outside technical support and minimize training needs, so by sitting and listening to the training in progress we could observe what was easy and what was hard to learn, which parts of the app make sense and which are confusing. I returned motivated and inspired, and filled with ideas about how to improve the tools, for example, printing a report to a PDF, choosing a file name, and interacting with the filesystem was a real challenge for users and we can simplify this workflow. It is inspiring to work holding in mind the amazing team of people who are on the ground in Peru using MAPEO to gather critical evidence of the ongoing environmental abuses, in the hope that this evidence will make a real difference and begin to improve their lives and reduce contamination of this precious corner of the Amazon Rainforest.

We are ever grateful to our partners who welcome us into their communities and territories with such enthusiasm, sharing their experiences as land defenders with us and being key collaborators in technology that can be used in other communities worldwide.

To learn more about MAPEO and how are partners are using it to defend their territories visit mapeo.world

If you are interested in the technical workings of Mapeo, all our development is happening in the open on GitHub where you can follow along and, if you have time and the skills, jump into the issues and help us fix some things.