author: Emily Jacobi

date: 2020-06-24

slug:

title: Indigenous Cartography & Decolonizing Mapmaking

wordpress_id:

categories: – blog

image: https://images.digital-democracy.org/assets/0-_am93ywhmouc4atu-1600@2x.png

–

It’s June 2020, and while the Coronavirus Pandemic is disproportionately affecting people of color around the world, here in the United States more and more people are turning their attention to another disease that has also taken far too many lives, but been with us for much longer – the disease of white supremacy.

White supremacy shapes all aspects of our lives, but one area where I don’t see it discussed often enough is in mapping. Over the years, Digital Democracy has worked on a variety of mapping projects, from mapping human rights violations in Southeast Asia to supporting disaster relief mapping in Haiti & Chile. And for much of the past decade, we have worked on participatory mapping projects with Indigenous communities in Central & South America. From these partners we have learned a great deal about both the problems with traditional GIS approaches, and the potential for more participatory & decolonized methods. While this article focuses on mapping initiatives with Indigenous peoples, it’s relevant to any approach to mapping that seeks to destabilize white supremacy and center the leadership of BIPOC – Black, Indigenous & People of Color. It is our hope that in reading about our experiences, other mappers and GIS specialists can be inspired to investigate their own biases and work to decolonize mapping. This article is adapted from talks given at State of the Map US and Personal Democracy Forum, and deeply informed by years of work in close partnership with Indigenous partners in South America, in particular the Waorani people whose story is featured below.

It’s taken me a long time to fully grasp it, but the more I learn about maps, the more I’ve realized they shape just about everything – good, bad & otherwise – about the society I live in. My love for maps started long before I co-founded Digital Democracy (Dd) in 2008. I even worked in a map store in college. But as our work at Dd has increasingly involved mapping projects in recent years, I’ve been at times humbled — and even ashamed — by how uninformed assumptions, even when coming from good intentions, can create immeasurable harm when they are embedded in our maps. So, if you consider yourself a mapper, someone who loves maps, someone who works with GIS data, or someone interested in visual storytelling, perhaps this story will be relevant to you.

What kind of world are we building with our maps?

How many of us take the time to ask this when we sit down with our tools (whether pen & paper or state of the art software) to draw our polygons and lines? And yet to make a map — and publish it, or define a congressional district with it, or profile where protests for Black Lives Matter are happening — is an act that affects the world. With our maps, we can reify old biases, or we can open people’s hearts. We can further entrench corrupt power systems, or we can call for a more just future.

The truth is that maps have been used as a tool to enable slavery, genocide, and massive land theft. They were critical to the European conquest of the Americas. While the practice of mapping as indigenous erasure may seem like a relic of the past, the shapes drawn to accommodate eurocentrism have defined the world that we live in today, and maps continue to be used to justify the theft of Indigenous land.

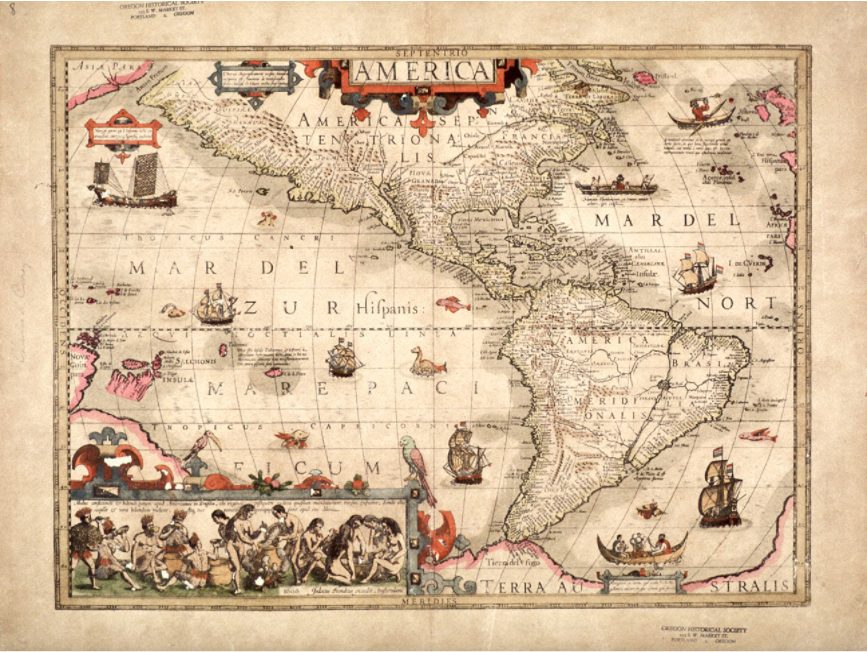

Map of the Americas, 1606, by Jodocus Hondius, from the archive of the Oregon Historical Society.

Above is a map of the Americas in 1606. I grew up seeing maps like this and used to linger on the monsters in the ocean, with childlike curiosity for a time of beasts. But as I learned more about the world, maps like this one started to shift. The monsters faded into the sea as the land mass came under harsh light. As a current resident of the so-called United States, I live in a hemisphere that has and continues to be populated by incredible civilizations —more than 800 nations and tribes estimated in North America alone, with complex religions, cultures, and societal rules — all living together on this land.

And yet the map says “Francia” and “Brasil,” names imposed from outsiders. Clean cuts of land are labeled according to the conqueror, disappearing Indigenous peoples from their rightful place.

Why is that?

Something I’ve learned from Indigenous scholars like Steven Newcomb is that the erasure of this continent’s Original Peoples didn’t happen accidentally, it was a purposeful policy of European church and state. Critical to this history is learning about the Doctrine of Discovery, which originated in a series of edicts written by popes in the 15th century that proclaimed the concept of “terra nullius,” (or “nobody’s land”) as any territory occupied by non-Christians. This doctrine literally encouraged European powers to go forth & conquer new lands, and to either kill, enslave or convert the non-Christians and take control of their territory. How many of the horrors of history & the injustices of our current moment can be traced in part to this doctrine of Euro-Christian supremacy?

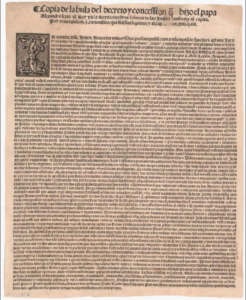

Pope Alexander VI’s Demarcation Bull, May 4, 1493 (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History).

Pope Nicholas V delivered the first law of the Doctrine of Discovery in 1452 to Portuguese sailors navigating the coast of Africa. The pope commanded that they capture and subdue all pagans and enemies of Christ, put them into slavery, and take away their property.

The doctrine was further edified in 1493, when Pope Alexander VI announced to the Spanish crown, upon landing in the Caribbean:

We, by authority of almighty God, give to you forever all islands and mainlands found, to be found, discovered, and to be discovered, towards the west and south, from the Arctic Pole, to the Antarctic Pole, and we appoint you and your heirs Lords of them with full authority and jurisdiction of every kind.

The doctrine guided the entire European conquest of the Americas and US law still rests on this framework regarding land rights. Despite its devastating legacy, it has never been annulled.

Many of the basic lines that sought to erase the existence of Indigenous peoples are still the same. The maps that we build upon and navigate today do not reflect the land as it once was, or even as it is, but by how it is perceived through colonizers’ eyes.

By making these invisible rules visible, we make room for an expanded concept of mapping that isn’t rotten at the roots.

The good news is that there are many examples of hope for a new mapping process and opportunities for decolonizing the way we build them.

The Decolonial Atlas

Let’s begin with a few examples from one of my favorite resources, The Decolonial Atlas.

This example challenges our very notion of a map as a two-dimensional object. What about a map that can fit in a mitten and can be read in the dark, that floats and suffers no damage if dropped in the sea? This is true of the maps of Inuit people in Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland), who traditionally carve portable maps out of driftwood, which are used for navigating their windy coastal waters.

“These three wooden maps show the journey from Sermiligaaq to Kangertittivatsiaq, on Greenland’s East Coast. The map to the right shows the islands along the coast, while the map in the middle shows the mainland and is read from one side of the block around to the other. The map to the left shows the peninsula between the Sermiligaaq and Kangertivartikajik fjords.” (Decolonial Atlas)

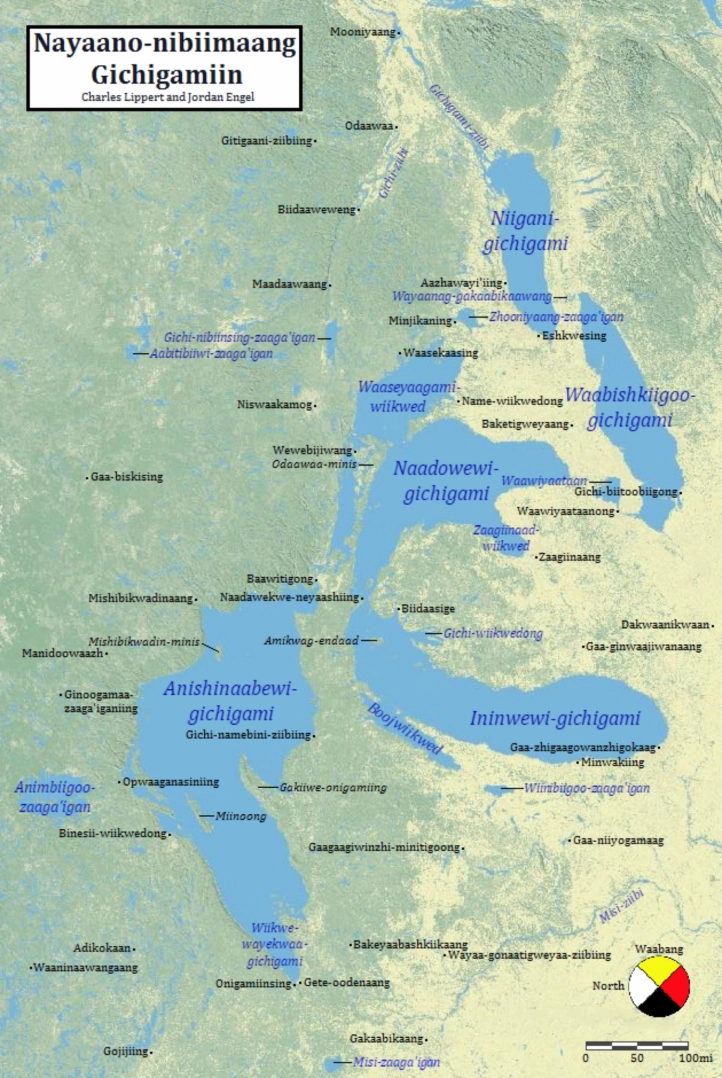

Here is another example from the Decolonial Atlas that challenges how we orient our maps. Do you recognize these bodies of water?

Although this is a familiar two-dimensional map with green & yellow representing land, and blue representing water, it challenges a basic assumption of European mapmaking by orienting the map towards the east rather than the north, because East (Waabang) is the orientation used in Ashinaabemowin culture. The compass rose itself is in the form of a medicine wheel, an Indigenous symbol used across the continent to denote the four directions.

“Nayaano-nibiimaang Gichigamiin” means “The Five Freshwater Seas” in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe). I grew up in the Great Lakes region, in so-called Indiana, and these lakes had a huge imprint on me as a child. And yet as a student in Indianapolis, I barely learned anything about the original inhabitants, or about the Native peoples still living in the region today. But the cultural impact of the Anishinaabe on the region is everywhere, as evidenced by this map, and in the now anglicized names. Mino-akiing (At the Good Land) became Milwaukee, WI. Odaawaa became Ottawa, Ontario. Gaa-zhigaagowanzhigokaag (At the Place Abundant with Skunk-grass) became Chicago, Illinois.

Counter Mapping, Indigenous Voices & Mapping from the Ground Up

In contrast to colonial mapping, there have been efforts for decades to displace colonial mapping approaches & center Indigenous leadership in mapping. An example of this is the work that we’ve done at Digital Democracy to support the Waorani Mapping project in Ecuador, led by our partners Alianza Ceibo and Amazon Frontlines.

“Our Rivers Aren’t Blue” – An In-depth look at the Waorani Mapping Process

The Waorani are an Indigenous people who live in the east of the Ecuadorian Amazon. They have lived on their territory for thousands of years and have effectively fought against different waves of invasion, from the Inca to the Spanish conquistadores, from rubber plantations to American missionaries and oil developments. Even as Waorani people have increasingly interacted with the outside world in recent years, they maintain ongoing customary practices and connection to their territory.

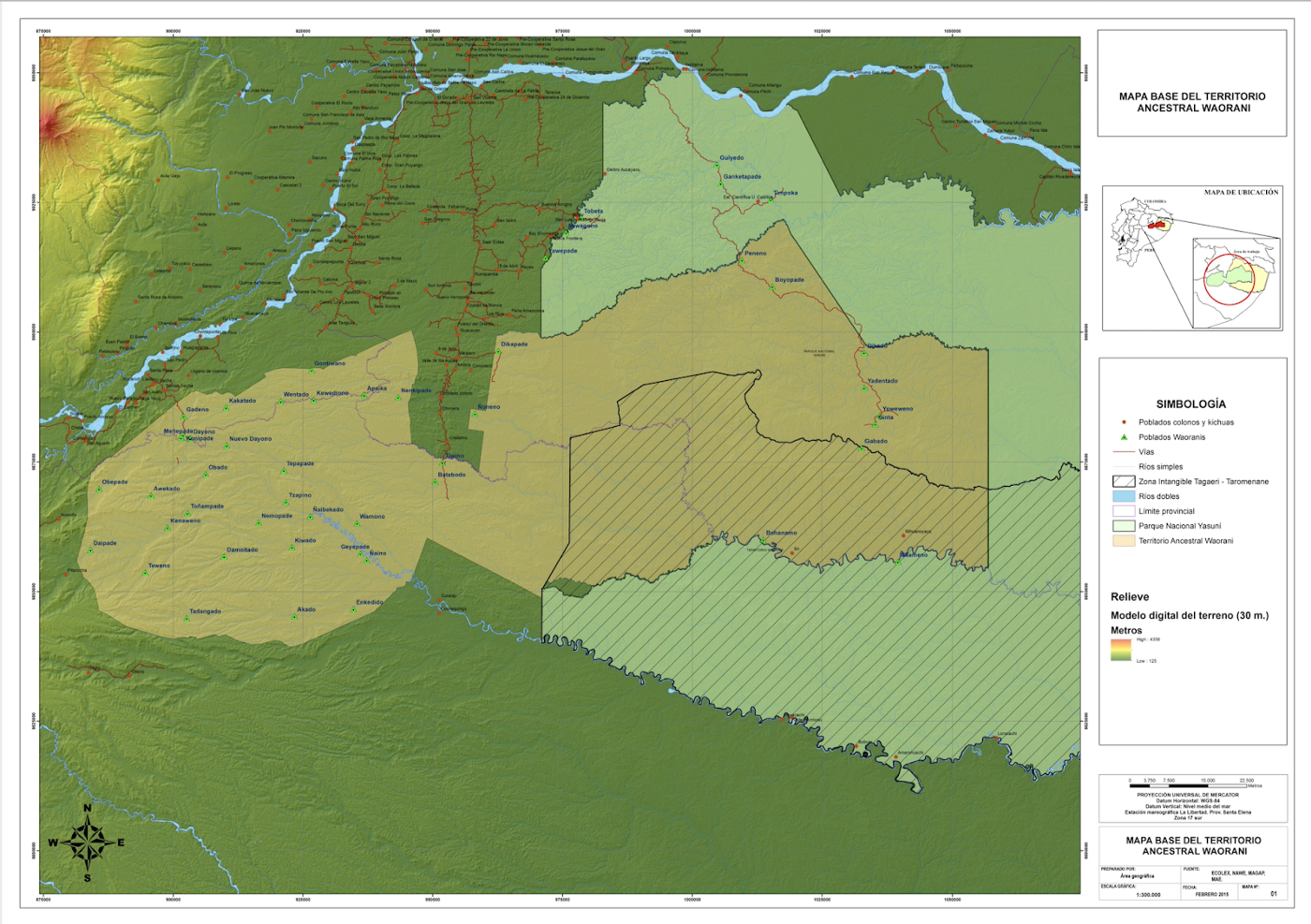

This map shows the territorial boundaries of the Waorani people. Unmarked are the laws influenced by the doctrine of discovery that grant the Waorani people title to the land but deny them rights to subsoil resources, such as oil and minerals, dividing up what is for the Waorani an integrated and indivisible territory.

This map shows the territorial boundaries of the Waorani people. Unmarked are the laws influenced by the doctrine of discovery that grant the Waorani people title to the land but deny them rights to subsoil resources, such as oil and minerals, dividing up what is for the Waorani an integrated and indivisible territory.

This map style is typical of maps made for official purposes and circulated by and for the Ecuadorian State. It is dominated by empty green forest and suggests little human presence, save a few village dots. Maps like this one make it easy for the government to sell off Indigenous territory for oil blocks, which happened in some parts of Waorani territory: the red line entering Waorani territory in the east marks a road built by the oil company to access its drilling platforms and pipelines.

Many Waorani people saw the devastating impact of oil on their cousins in the eastern part of their territory. They began working with Alianza Ceibo and Amazon Frontlines to try and prevent drilling in their territory by creating “a map full of things that don’t have a price.” The mapping team tested a variety of different applications but none were a good fit for their offline environment and collaborative mapping process. In 2015, they reached out to Digital Democracy and asked us to help support their mapping process.

The Mapping Process

As of 2020, we have completed the following mapping process with 20 of the 52 villages.

Drawing board: The process begins in a participatory way with paper & markers. Everyone in the community — men, women, elders, children — is invited to come and draw their knowledge of the territory across large sheets of paper. This process makes visual the community’s deep intimacy with the unique history, resources, and features of their home, in addition to making an opportunity for elders’ voices and stories to be heard by younger generations. Once the paper mapping is complete, the community decides which features are important to document. A designer turns these items into unique symbols that will comprise the legend.

Walkabout: The mapping team goes on walks with village elders and knowledge-holders to collect GIS data using handheld GPS devices as well as oral testimony and stories about important features, such as palm swamps, fruiting trees, animal mineral licks and fishing spots.

Data entry: Back in the village, the team enters the GPS points into Mapeo Desktop, as well as additional information and stories. A variety of background maps from satellite images are used to help locate geographical features. Once the data points are uploaded, the map is projected on a wall for the whole community to see.

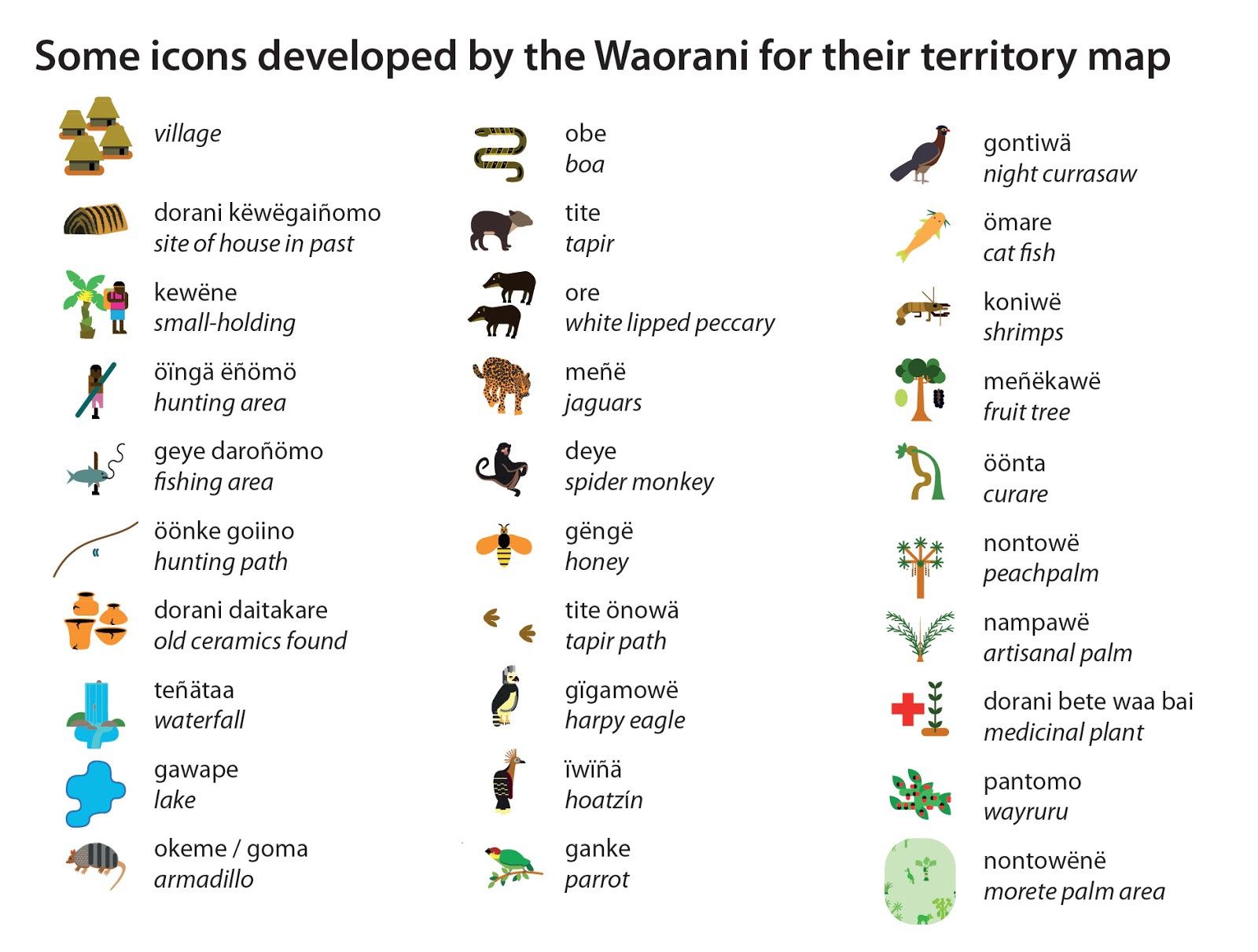

Lexicon: The data is entered using the unique symbols within the legend. The Waorani legend contains over 150 items, from jaguar paths to clay deposits, ancient burial sites to flying ant nests.

Export: The data is exported from Mapeo to GeoJSON, and then uploaded into Mapbox where the design template is stored. Legend and titles are added using illustrator.

Print: Draft maps are sent to each village for further editing and verification. Finalized maps are then printed and given to each family in the village.

Here is a detail from one of the first maps created during the process, from the village of Nemonpare:

And here are just a few of the over 150 icons they have created over time:

Working closely on the maps over the past five years, we saw the ways the mapping team constantly negotiated between making maps that reflected & reinforced the way Waorani people see their territory and awareness of an external audience.

Working closely on the maps over the past five years, we saw the ways the mapping team constantly negotiated between making maps that reflected & reinforced the way Waorani people see their territory and awareness of an external audience.

One example of this is how to represent water. For anyone who, like me, grew up with Eurocentric maps, we assume that blue is the color for water. And yet our Waorani friends were puzzled by this. There are many rivers in Wao territory. Some are green, brown, even black depending on the rains and the season, but they aren’t blue.

In the end, they decided to use blue on the maps to make them more legible to an outside audience, but it was a process that revealed to me just how little I had actually paid attention to the color of rivers before. It’s just one of the thousands of examples of how a structure of knowing such as “water is blue” can hold us back from seeing what’s right before our eyes.

The maps were first and foremost created for the Waorani people, but from the beginning, the villagers understood that the maps could ultimately be used as a tool to communicate their vision of their land to the outside world. In 2018, this proved invaluable when the Ecuadorian government announced a massive sale of new oil blocks that encompassed over 7 million acres of Ecuadorian rainforest, including Block 22 — the Western part of Waorani territory where we had been mapping.

The community decided to launch a legal case against the government to fight the sale, and we helped them publish an online mapstory showcasing their message for the accompanying campaign. This map told a different story from the government’s green emptiness — one rich with characters and history, one in which every single vibrant acre of the territory in question would be threatened by oil production, from Waorani cultural traditions to the many plants and animals who live on their land.

In 2019 the Waorani won the lawsuit when the national court ruled that the Government had not carried out adequate consultation before creating the oil blocks, violating the communities’ rights to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC). The oil block was removed and ½ million acres of the Amazon were protected. The case set a major precedent for indigenous action within Ecuador and across the globe. Read more about this in my colleague Aliya’s account of the role of the maps in the legal process.

“The map will speak to the world and show the life we want to protect. We can show the map to the neighbors. This is a story that I can show to my grandchildren. Through this, they will know the work I have done.” — Waorani elder Dika, one of the leaders of Kenaweno.

The Role of Technology in Decolonizing Mapping

Whether we’re aware of it or not, things like the Doctrine of Discovery continue to shape our lives, from our maps to our laws. When maps show territory that is empty, it is easy to buy into the false belief that it is “nobody’s land” and that the government has the right to sell it off. When Indigenous peoples make their own maps that affirm their rich cultural heritage & deep connection to local ecology, it starts to change the equation and helps the rest of us question our own assumptions that have been shaped by Eurocentrism & white supremacy.

“Technology won’t save our land. We have to save our land.” — Opi Nenquimo, director of the Wao Mapping project

The process of mapping helped the Waorani build an argument for why their land would be threatened by oil. It also laid the groundwork for Waorani from different villages to form consensus to take action against the sale. The collaborative mapping process strengthens shared memory and relationships.

“I remember being a child when the Evangelists came here. Over the past 40 years, they & others have talked to us about maps, but they are from the outside, and bring other people’s ideas about our territory. But I walked for two months to make this map. When we are in meetings with the government ministries, and they show us maps of our land and our communities, I can take out our map and show them how it really is.” — Nihua Quimontasi

There are plenty of tools available today that can collect data offline, but very few of them are designed to transform that data into locally empowered data management. This common oversight has normalized a data collection process that is inherently extractive, obfuscating even the best of intentions through assumptions embedded in design, which too often serve an end-user who is far removed from those collecting the data.

When we started building Mapeo seven years ago, we set out to build a free tool that makes it easy for local communities to collect data offline, and manage that data locally. As an organization, we prioritize data solidarity and local-first principles in the development and assessment of our tools.

Mapeo has come a long way since we began working with the first Waorani village of Nemonpare, thanks to their help co-designing the tools & processes. The progression of these tools over time has been directed by the unique needs of local communities that we work with. Today, Mapeo allows users to use both mobile & desktop tools to map baseline territory information, such as sacred sites and rivers, and to track ongoing monitoring information such as oil spills and illegal logging.

Mapeo is currently being used by over 150 frontline land defenders to monitor and defend almost 10 million acres of indigenous lands from environmental and human rights abuses, serving over 14,000 people, and has been used to map over 700,000 acres of ancestral lands.

Further Reading:

To learn more about Mapeo, visit http://mapeo.app/

To read more about the Waorani mapping process, read my colleague Aliya Ryan’s article, “Our Rivers are not Blue: Lessons, Reflections and Challenges from Waorani Map Making in the Ecuadorian Amazon.”

You are on Native Land: At Dd, we are committed to the practice of learning whose land we are on & acknowledging the traditional peoples of the territory. Native-land.ca is an important resource for this.

For other examples and information about Indigenous & Counter Mapping, see:

- The work of the Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project from the 1970s

- The analyses of Renee Paulani Louis, an Indigenous Hawai’ain academic and cartographer

- Emergence Magazine’s profile on Zuni Counter Mapping

- Guardian article discussing counter mapping as subversive storytelling device for the marginalized

- Oxfam blog listing a range of great initiatives and resources for community mappers

Watch this short documentary about the Wao mapping process, featured by Al Jazeera.